Styling & Visual Storytelling

I love words. I love their ability to conjure up an image, and their simultaneous frailty when it comes to exactly describing something. There just might be the perfect words out there, and finding them is so illusive. It's that ongoing search—the game of it—that makes writing so appealing.

Yet I would be remiss, foolish not to admit that a good image has a descriptive power separate from that of words. Not better or worse, but certainly important. The strongest messages come from thoughtfully pairing well crafted words and imagery.

Apple-strawberry hand pies and mini chai-cream pies from Stephen's and my first food shoot. Perhaps its my love of gluten-free desserts, but I continue to find that baked goods have a photogenic quality that makes them easier to style.

I have always had an appreciation for strong and beautiful images. But I did not understand that the people behind those pictures, specifically the stylists, have to have a strong sense of story if they are going to construct something meaningful.

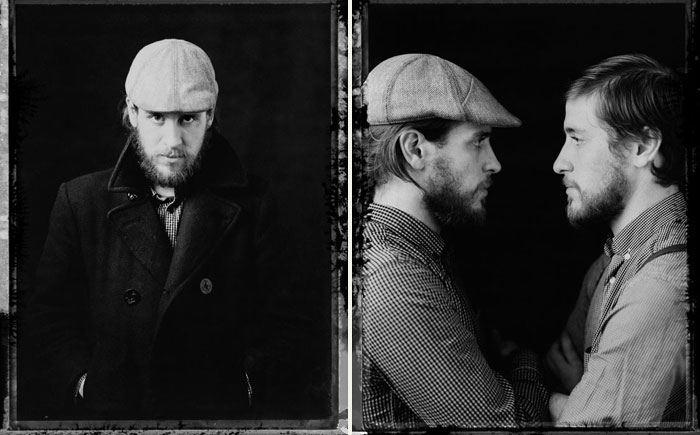

I started styling when I thought that I might create a gluten-free food blog. I had recipes I enjoyed making, and wanted to share them. I also had the good fortune of being married to a photographer with a growing interest in food photography. The first time we put together a food shoot, I made a series of pies. We created two shots that were moody, but still gave a clear sense of what was in the pies. They remain some of my favorites—I think because the shots came together so naturally.

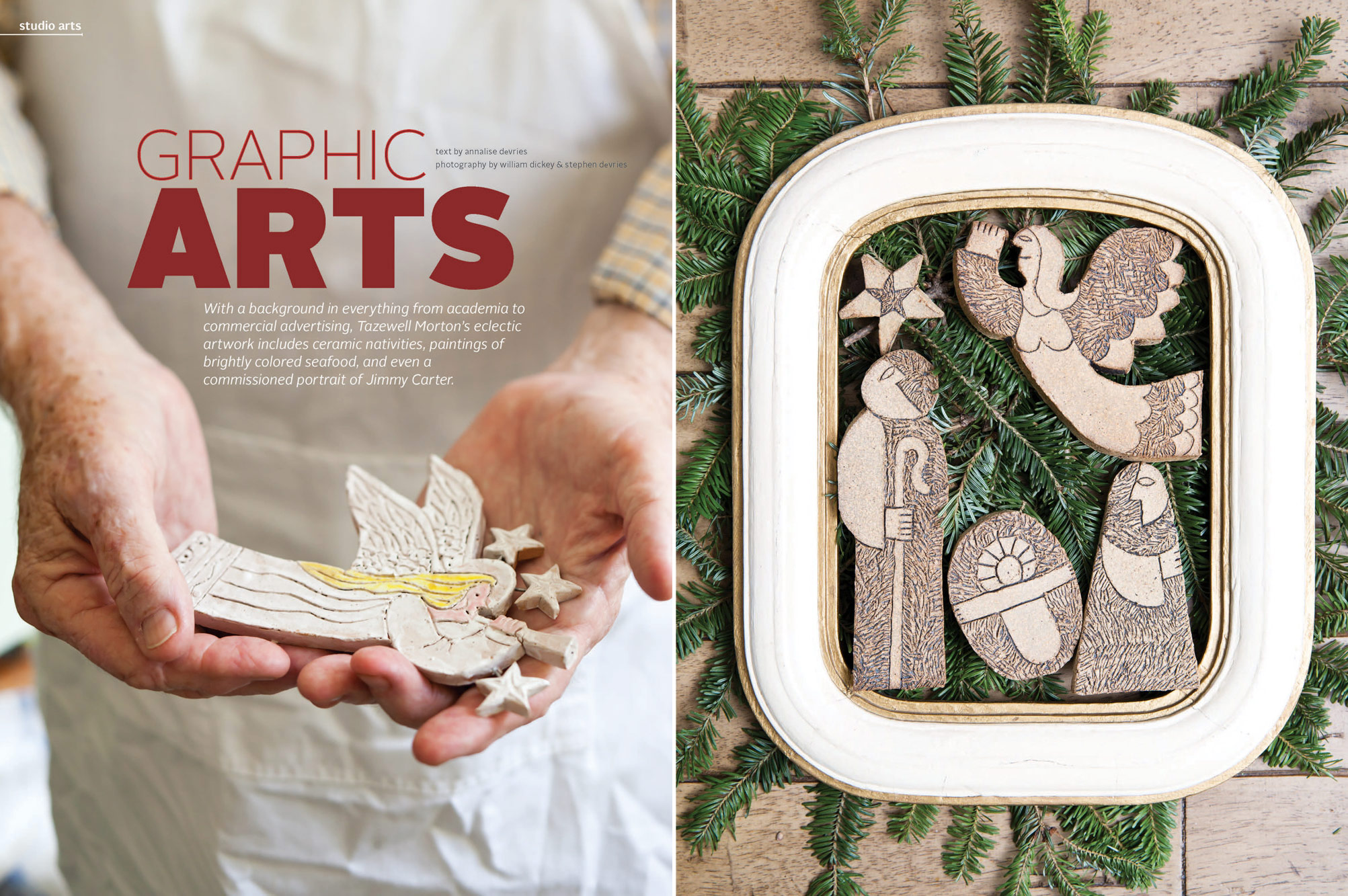

That first shoot was a bit of a tease. A few months later, when I got my first styling freelance assignment for fresh style, I was less sure of myself. Without constructing the recipe and executing it, I didn't have a clear sense of what the picture needed to communicate and how I was supposed to contribute to it. It was only with the help of my editor that I began to fully grasp that without using any words, my job as the stylist was also to tell a story.

One of our first collaborations for fresh style, where Stephen took the photos and I was charged with writing and styling. We were there in September, and had to make this Ohio greenhouse look like it was the middle of spring.

A lot goes into that kind of visual storytelling. If it's a home, where does the throw blanket go so that it looks natural, but not sloppy? If it's food, how do you place the utensil so that the fare looks all the more enticing? Simple decisions can bring these inanimate objects to life, or make them look awkward and out of place. So often it boils down to instinct, taste, and a good eye.

Some people mistakenly think that styling means faking something or creating impossible standards. Yet a good stylist knows that the best stories are approachable and subtly inspiring, but are never overpowering or didactic.

The best styling you never notice. It's like a well-constructed sentence, so naturally crafted that the reader doesn't imagine a writer behind it, but merely absorbs it as something of his own. Likewise, the stylist is often the unsung hero of the photo shoot. She has researched the right props, and found the ideal location. She understands all of the visual pieces that need to come together to convey the narrative. Then she collaborates with the photographer to bring it all together.

While I now spend most of my time writing, and this blog instead focuses more broadly on creative processes (which sadly only sometimes involves gluten free desserts), I still get to keep a toe in the food and prop styling world each month, when Stephen and I shoot the monthly manual for The Mantry Company.

Mantry is a masculine food-of-the-month club, that offers six well-curated artisan food items to their customers each month. In addition to the food, they send along a manual with simple recipes. They are fun stories to tell—Thanksgiving leftovers turned into shepherd's pie, a bourbon breakfast, even a cocktail party how-to that was featured in GQ.

Yummy shrimp skewers from Mantry's grilling manual.

These shoots are a fresh reminder of the central importance of good, thoughtful styling. They help sharpen the visual side of my creativity, and allow me to leave the words behind for a minute and consider a different narrative form.

They are also a humbling reminder that the next time I see a beautiful picture I love, to not only appreciate the photographer, but also look for the stylist behind the story.