Analog and Digital: CineStill Film and the Brothers Wright

When I sit down to write, I generally need a pencil and a few scratch pieces of paper. I might do 90 percent of my composing on the computer, but those analog tools remain essential to my writing process. Sometimes the words start to flow, but my thoughts somehow get jumbled on the way from my brain and the keyboard. I need my thoughts to slow down, so I stop typing, pick up my pencil and jot down the sentence I'm trying to articulate. The change in rhythm helps me clarify my thoughts. The words start to untangle themselves on the page, and I’m soon back to typing.

“People are now discovering that all important things in reality have an analog beginning and end, and the digital world is just one step between one analog experience and another.”

When it comes to using a word processor or writing by hand, it's not an either/or choice. I need both. The two methods support and reinforce each other, and hopefully make me a better writer in the end. What I've recently come to see—thanks to some incredibly thoughtful and creative friends—is that this cyclical relationship between the analog and the digital is not just about writing, it's really a way of understanding the many creative possibilities that surround us.

For fresh style, we ran a web series on the modern craft of film photography, and talked to photographers Brandon and Brian Wright (jointly known as the Brothers Wright) about their creation of CineStill Film. Their work makes motion picture film available to still photographers—something unheard of in the past. Now, they’re in the midst of a Kickstarter to expand production to a medium format film. In the freshstylemag.com story, I explored what their invention means to film photographers. I think their work sends a bigger message, though, to anyone interested in innovation and creativity, regardless of whether or not you pick up a camera or can tell a light meter from a flash card.

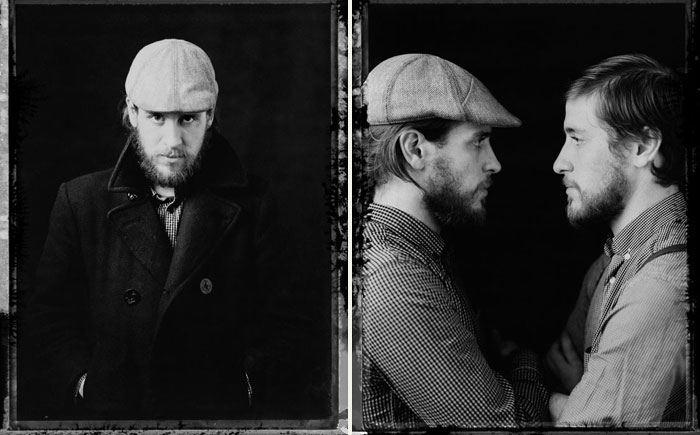

Portraits of the Brothers Wright by Stephen DeVries. (Left: Brandon Wright; Right: Brandon - left, Brian - right).

I asked Brandon and Brian about their take on the relationship between digital and analog. Knowing that they're dedicated film photographers, I wanted them to actually explain why film still matters in our digital age. Brian responded that he believes we’re entering a “post-digital” Renaissance.

“Digital is no longer a new and shiny ‘revolution,’” he continued. “People are now discovering that all important things in reality have an analog beginning and end, and the digital world is just one step between one analog experience to another.”

Brian’s point helps explain why there’s a growing market for vinyl records and vintage typewriters; why there’s a return to handicrafts, and you can attend entire fairs dedicated to carefully spun fibers. People are discovering their most meaningful present by returning to older forms of creativity that have them using the same methods generations earlier employed. It’s not about finding an altogether new creation, but a more mature understanding that what we do now confidently stands on the shoulders of those who came before us.

The Brothers Wright are embracing the modern growth of analog with more dedication than most. Supporting their expansion of CineStill is an opportunity to participate in a new innovation that is as deeply connected to the past as it is relevant to the present. I can’t invent a new pencil and paper that will help me develop as a writer. For me, that’s all the more reason to help support the development of an important new tool for other creatives.